When Abstraction Became an Act of Defiance:

Les Automatistes and the Fight for Intellectual and Spiritual Freedom in 1940s Quebec

Abstract art has rarely been politically neutral. Across the twentieth century, it was repeatedly branded as dangerous, elitist, immoral, or subversive—not because it carried explicit political slogans, but because it refused to do so. Its ambiguity, its emphasis on individual perception, and its resistance to fixed meaning made it profoundly difficult to control. In authoritarian or clerically dominated societies, abstraction has often been read as a form of rebellion against imposed order.

In mid-1940s Quebec, this dynamic played out with particular intensity. The emergence of Les Automatistes in Montréal was not simply an art historical development; it was a direct challenge to a rigid, repressive social order in which Church and state tightly regulated cultural, intellectual, and spiritual life.

Quebec in the 1940s: A Controlled Moral and Cultural Order

When Les Automatistes began gathering in Montréal, Quebec was governed by Premier Maurice Duplessis and his Union Nationale. This period—later termed la grande noirceur (“the Great Darkness”)—was defined by a powerful alliance between government, Catholic Church, and conservative cultural elites.

The Church controlled education, health care, and much of social policy, reinforcing obedience, moral conformity, and suspicion toward secular, socialist, or avant-garde ideas. Cultural production was expected to uphold Catholic values and a mythic, rural French Canadian identity. Art that was legible, didactic, and morally reassuring—religious scenes, idealized landscapes, and conservative portraiture—received institutional support.

Modernist experimentation, by contrast, was treated as suspect or dangerous. Censorship of books, films, and performances was broad, public libraries were scarce, divorce was effectively impossible, and dissent—political or cultural—was chilled by legal tools such as the Padlock Act, which allowed authorities to shut down spaces accused of spreading vaguely defined “communist” ideas.

This environment did not simply shape culture; it constrained thought itself.

Abstraction as Spiritual and Intellectual Rebellion

It was within this suffocating atmosphere that Paul-Émile Borduas and Les Automatistes embraced Surrealist automatism—spontaneous, subconscious mark-making—and increasingly non-representational abstraction. Their work rejected academic discipline, clerical authority, and the idea that art must serve moral, national, or ideological ends.

To paint without premeditation, without narrative clarity, without obedience to tradition, was itself a radical gesture. Automatism proposed that truth resided not in imposed doctrine but in the individual psyche—in intuition, impulse, and lived experience. In a society structured around obedience and hierarchy, this insistence on personal freedom was revolutionary.

Abstract art, in this sense, was not an escape from reality but a refusal of an oppressive one. It offered a space in which the soul could breathe.

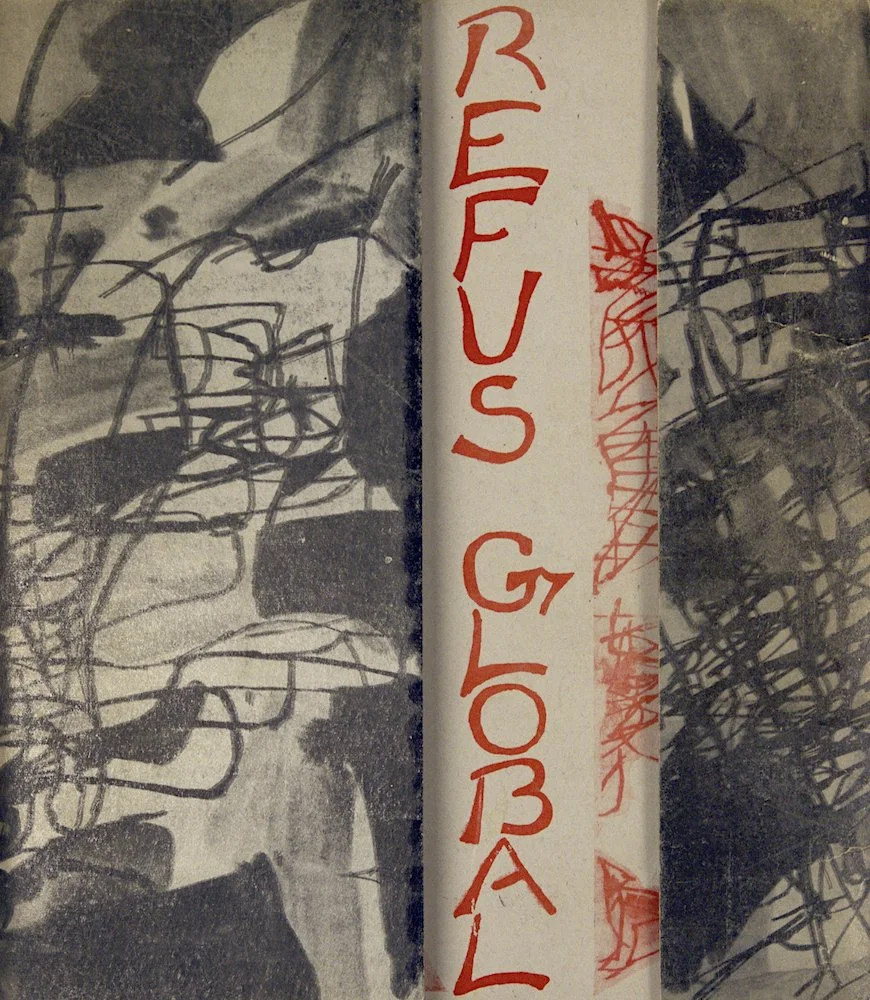

Refus global: Naming the Suffocation

(In 1948 Borduas wrote the automatist manifesto Refus global as an introduction to a collection of writings signed by himself and by fifteen other artists — Madeleine Arbour, Marcel Barbeau, Bruno Cormier, Marcelle Ferron, Claude Gauvreau, Pierre Gauvreau, Muriel Guilbault, Fernand Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Maurice Perron, Louise Renaud, Thérèse Renaud, Françoise Riopelle, Jean Paul Riopelle and Françoise Sullivan.)

The conflict between Les Automatistes and Quebec’s power structures became explicit in 1948 with the publication of Refus global. The manifesto denounced the “suffocating” authority of Church and state and called for absolute freedom of thought, expression, and creativity.

The response was swift and punitive. Borduas was dismissed from his teaching position at the École du meuble de Montréal and effectively blacklisted. Other signatories—including Françoise Sullivan, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Marcel Barbeau, and Fernand Leduc—faced institutional exclusion and hostility. Several left Quebec altogether, pursuing their careers in Paris or elsewhere, where abstraction was not criminalized by moral doctrine.

The message was clear: modernist, individualist art was perceived as politically and spiritually dangerous.

A Global Pattern of Fear

Quebec’s hostility to abstraction was not unique. Across the twentieth century, regimes that demanded ideological clarity repeatedly attacked modern art.

In the Soviet Union, abstraction was condemned as “formalist” individualism incompatible with Socialist Realism, which demanded clear narratives glorifying the state.

In Nazi Germany, modernist and abstract works were labeled “degenerate,” mocked in the 1937 Entartete Kunst exhibition, and purged from museums for threatening racial and moral order.

Even in the United States, Abstract Expressionism was at times attacked as subversive or unpatriotic—while simultaneously being weaponized during the Cold War as proof of Western individual freedom.

Across these contexts, abstraction provoked anxiety because it could not be easily instrumentalized. It foregrounded ambiguity, interiority, and nonconformity—qualities that resist authoritarian control.

Les Automatistes and the Freedom to Imagine Otherwise

In Duplessis-era Quebec, abstraction and automatism became coded acts of resistance. The Automatistes’ studios, manifestos, and informal networks formed an oppositional culture that challenged clerical nationalism and moral regulation. Their art imagined a Quebec not defined by obedience, rural myth, or religious authority, but by secular thinking, personal freedom, and creative risk.

Although marginalized at the time, their impact was profound. The values articulated in Refus global—freedom of expression, separation of Church and state, openness to modernity—anticipated the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, when Quebec rapidly secularized and redefined its cultural identity.

Why This Still Matters: Art, Freedom, and Cultural Stewardship

Today, Les Automatistes are rightly recognized as foundational figures in Canadian modernism, and their works now occupy a central place in museum collections, academic scholarship, and the international art market. Major paintings, works on paper, and sculptural or interdisciplinary pieces by artists such as Paul-Émile Borduas, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Marcelle Ferron, Françoise Sullivan, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Fernand Leduc, Pierre Gauvreau and Marcel Barbeau command significant prices at auction and are actively sought by serious collectors worldwide. Their market value reflects not speculation, but historical weight.

AI generated image of an art auction

Yet the importance of these works extends far beyond their monetary worth. To collect Les Automatistes art is to engage directly with a moment when abstraction functioned as an ethical stance—a refusal of intellectual submission and a declaration of spiritual autonomy. These works were created at real personal risk, in an environment where freedom of expression could cost artists their livelihoods, reputations, and homeland. That history is embedded in the surface of the paintings themselves.

For collectors, acquiring works by Les Automatistes is therefore not merely an act of connoisseurship, but one of cultural stewardship. As prices rise and international demand grows, there is an increasing responsibility to ensure that significant examples of this movement continue to circulate within Canada, rather than being permanently dispersed abroad. Private collections play a crucial role in sustaining visibility—through loans, exhibitions, publications, and scholarly access—especially for works not held by public institutions.

Supporting the market for Les Automatistes art is also a way of honouring what these artists made possible. Their insistence on personal freedom, secular thought, and experimental form helped pave the way for the Quiet Revolution and for a broader reimagining of Quebec’s cultural and intellectual life. To collect their work today is to affirm pride in a legacy that challenged repression and expanded the boundaries of thought.

Ultimately, abstraction was dangerous because it trusted the individual. Les Automatistes insisted that meaning could not be dictated by Church or state, and that the soul required space to move freely. Preserving, collecting, and circulating their work ensures that this legacy remains active—not frozen in history, but alive within Canada’s cultural consciousness, reminding us that freedom of thought is something that must continually be protected, supported, and claimed.

What Our Reader's Say:

〰️

What Our Reader's Say: 〰️

“Thank you for this article, I did not know the history of this movement. Quebec certainly was a stronghold of religion and protection of the French language. I did not appreciate that this art was a rebellious act done at personal cost. Non conformity such as being a feminist and an atheist has had some personal cost to me particularly in the sixties and seventies. I now appreciate the historic value of this art. Thanks for another great read.” - Janice