Ronald Bloore at 100: The Artist Who Painted the Unseen

A centennial reflection on the legacy of one of Canada’s most rigorous and original abstract painters.

“I do not paint what I see; I paint the unseen.”

If Ronald Bloore were alive today, he’d be 100 years old. And somehow, you imagine he’d meet the milestone with a wry smile, a stiff drink, and a sharp critique of the very idea of celebration. After all, Bloore was never one to conform—not in life, not in art.

Born in Brampton, Ontario, in 1925, Bloore famously decided he would become an artist at just four and a half years old—provoked not by inspiration, but by contradiction. As he recalled with characteristic wit, the local Canada Bread man asked his mother if the boy drawing at the kitchen table would grow up to be an artist. Her reply: “Oh, no, there’s no money in that.” For Bloore, that settled it. He would be an artist.

Over the decades, Bloore became one of the most distinctive figures in Canadian art—painter, curator, art historian, teacher, provocateur. He’s best known as one of the Regina Five, a group of painters who, in 1961, stunned the national art scene with their abstract and experimental work. But even then, Bloore was the outlier among outliers. “We lived in the same city,” he once said of the group, “but there was no shared program. That would’ve been unthinkable.”

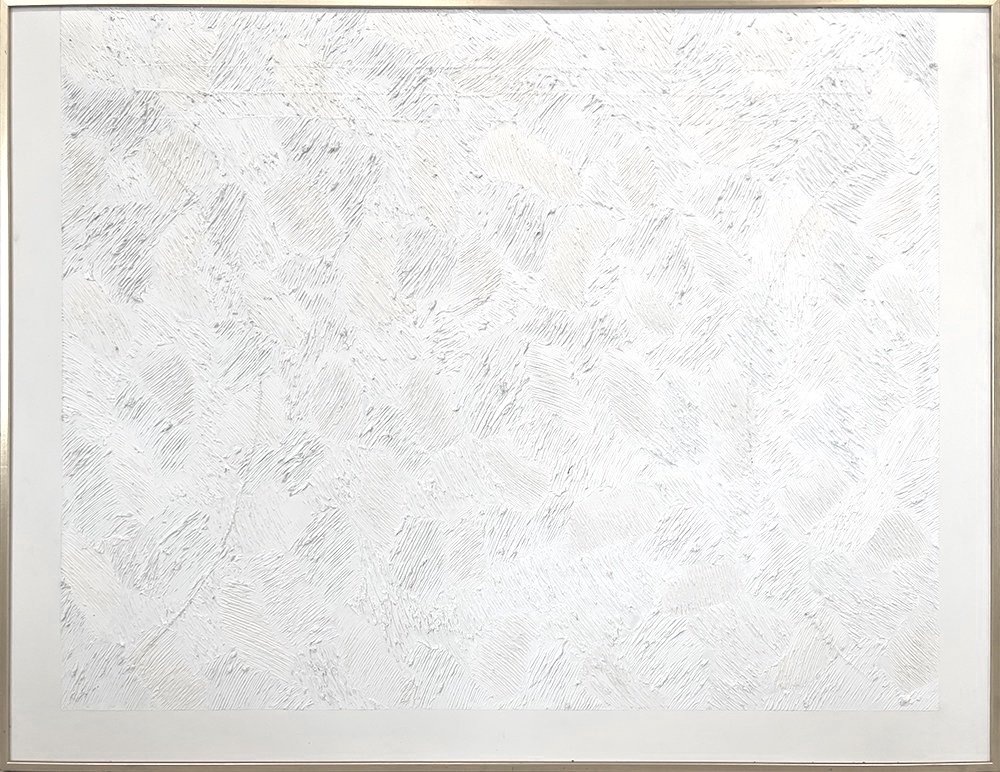

His own artistic program was fiercely individual. A painter of white paintings—restrained, formal, deeply textured—Bloore rejected trends, sentiment, and spectacle. He didn’t paint what he saw. He painted what couldn’t be seen. Inspired by ancient architecture, non-Western art, and early Mediterranean civilizations, his canvases are quiet meditations on form, order, and the timeless language of symbols.

Untitled, Dec. 1983 oil on masonite 48” x 63”

Private collection exhibited at the John Mann Gallery.

For Bloore, painting wasn’t about expressing emotion or chasing novelty. He believed everything that mattered in painting had already been achieved by the 13th century. Cimabue was, in his view, the last great painter. The Renaissance, with its illusionism and blue skies, was a mistake. The real revolution came later—with Kandinsky, Mondrian, and the abstractionists who, like Bloore, sought a purer visual truth.

And yet his intellectual rigor never made his work cold. Stand in front of a Bloore painting, and you feel presence. You feel architecture. You feel time. His signature white-on-white surfaces shimmer with quiet complexity—a kind of sacred geometry that invites not just looking, but contemplation.

Bloore also shaped Canadian art far beyond the studio. As director of the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina, he curated bold exhibitions, championed new talent, and helped raise the profile of Western Canadian painters. His legacy lives on in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and dozens of institutions and collectors across the country and beyond.

In his 100th year, we don’t just remember Ronald Bloore—we look again. We revisit the stark white surfaces, and in his later works, the bare masonite left intentionally unpainted, allowing form and texture to emerge without the need for pigment. We listen to his ideas, still bracing in their clarity. We remember the boy who insisted on becoming an artist, the man who painted the unseen, and the thinker who reminded us that art is a long, slow conversation with history.

Happy 100th, Ron. You saw what many of us missed—and showed us how to see it too.

Margie Galita, Hank Roest and Ronald Bloore. Installation day at Moore Gallery, Toronto, 2001