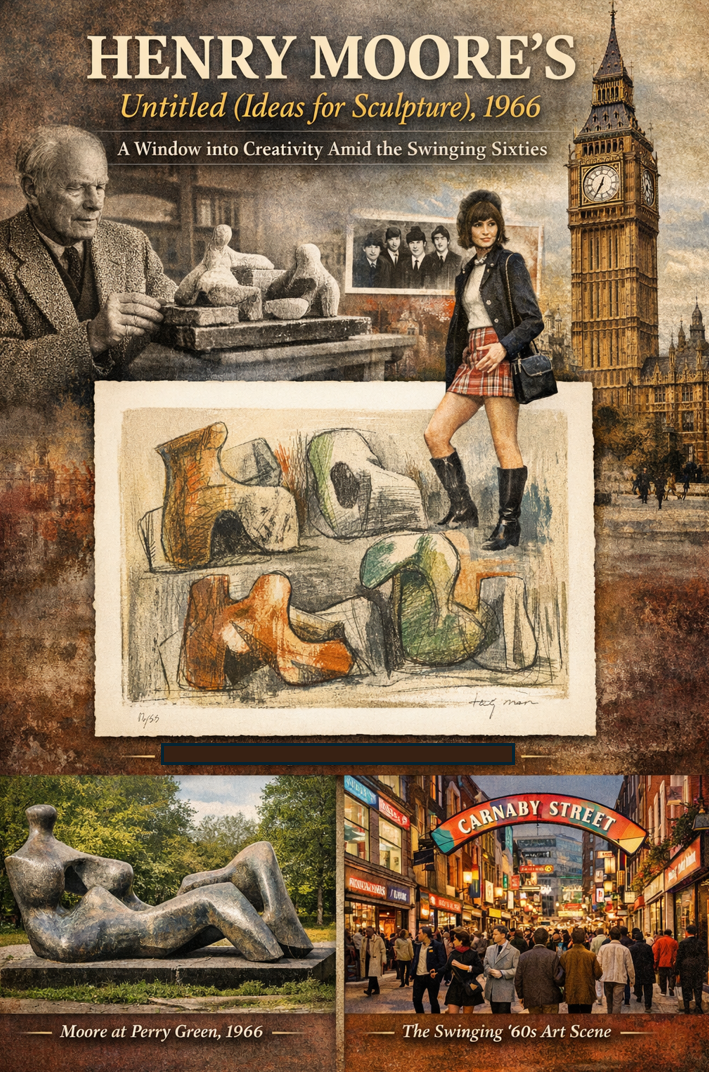

Henry Moore’s Window into Creativity Amid the Swinging Sixties

In 1966, England—and Europe more broadly—was at a crossroads. Politically, Harold Wilson’s Labour government was pushing modernization, investing in science, education, and infrastructure, while navigating the tensions of decolonization and the Cold War. Economically, post-war prosperity still lingered, though Britain was beginning to confront financial strains that would culminate in the pound’s devaluation in 1967. Socially and culturally, the “Swinging Sixties” were in full bloom: youth-led movements challenged traditional authority, fashion and pop culture flourished, and London became an international epicenter for music, style, and experimental art. The city’s underground scene—from Notting Hill to Soho—buzzed with experimental galleries, psychedelic art, and countercultural energy, while British Pop Art, abstraction, and Op Art were redefining the visual landscape.

Amid this vibrant, sometimes chaotic environment, Henry Spencer Moore (1898–1986) stood as a respected elder statesman of British art. At 68, Moore was living and working at his estate in Perry Green, Hertfordshire, a home and studio he had settled into during World War II. By the mid-1960s, Perry Green had grown into both a personal sanctuary and an incubator for his monumental sculptures—a sculpture park where bronzes were conceived, cast, and installed, blending natural landscape with humanist form.

Moore in 1966: Master of Monumental Forms

By 1966, Moore had achieved international prominence. He was actively engaged in large public commissions, including multi-part reclining figures and abstract works that would define the late stage of his career. A major work, Reclining Figure, had recently been unveiled at Lincoln Center (1965), and Moore continued producing large-scale bronzes in collaboration with foundries at Perry Green. This was also the year his writings and interviews were gathered into the influential volume Henry Moore on Sculpture, clarifying his philosophy on form, space, and the relationship between sculpture and landscape.

Moore’s presence in the art world remained strong: his work was widely exhibited across Europe and North America, and he was regularly featured in solo and group shows at institutions including the Tate, MoMA, and numerous sculpture parks and university campuses. Critics frequently highlighted his dual role as a creative innovator and an establishment figure, shaping not only public taste but also museum and gallery agendas.

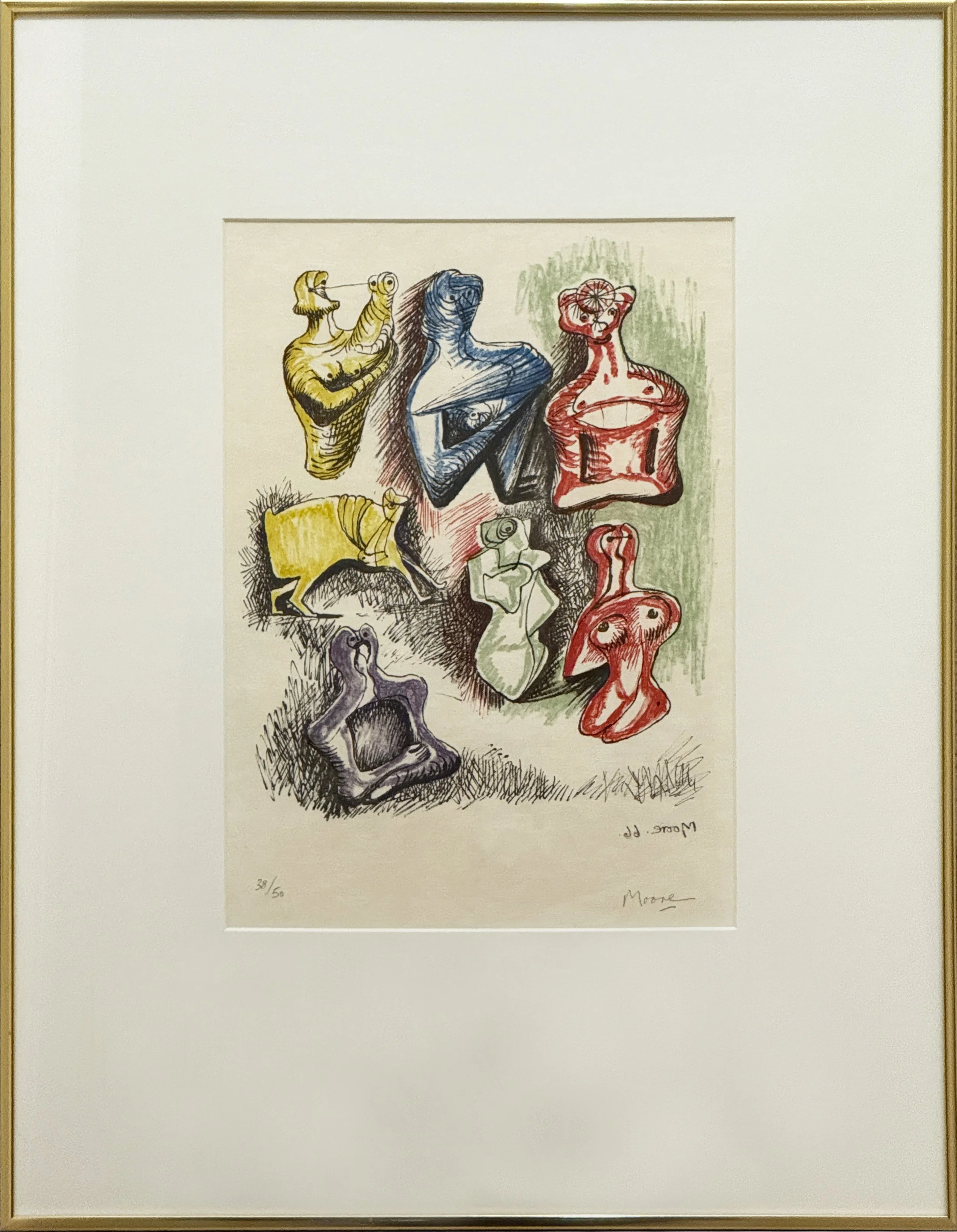

The Lithograph: Untitled (Ideas for Sculpture), 1966

Henry Spencer Moore (1898 - 1986) BRITISH

Title: Untitled (Ideas for Sculpture), 1966

Media: original coloured lithograph on paper

Size: 23” x 18”

Notes: Edition & Signature: Limited edition lithograph, signed "Moore" in pencil lower right and numbered 38/50 lower left, dated and artist signature printed reverse on bottom right of image

Against this backdrop, Moore produced Untitled (Ideas for Sculpture), 1966, a limited edition coloured lithograph on paper measuring 23” x 18”. Numbered 38/50 and signed “Moore” in pencil on the lower right, with the edition and date printed on the reverse, this work captures the artist in a reflective, experimental mode.

Unlike his monumental bronzes, the lithograph provides a glimpse into Moore’s conceptual process—his exploration of forms that would later be realized in three-dimensional sculptures. The work exemplifies his interest in the human figure abstracted into organic shapes, balancing mass and void, concave and convex, and the tension between natural landscapes and human presence. For collectors, this lithograph is more than a print—it is an intimate record of Moore’s creative thinking at a moment when he was navigating both artistic innovation and institutional prominence.

Moore Amid the Swinging Sixties Art Scene

While Moore worked methodically at Perry Green, London’s art scene was alive with experimentation. Pop Art, led by Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, and David Hockney, dominated galleries, blending advertising, comics, and celebrity culture. Abstraction persisted through figures like Frank Bowling, while Op Art and European avant-garde movements—from Bridget Riley to the German Zero Group—explored optical effects and kinetic experiments. In this context, Moore’s work represented continuity, humanism, and enduring craftsmanship—a counterpoint to the era’s flashy, youth-driven aesthetic.

Collecting Moore Today

For collectors, Untitled (Ideas for Sculpture), 1966 represents both historical significance and aesthetic value. Its limited edition, fine condition, and insight into Moore’s process make it a rare opportunity to own a piece of 20th-century art history. As institutions and private collections continue to celebrate Moore’s legacy, works like this lithograph remain highly prized for their embodiment of the artist’s enduring vision, bridging abstraction, human form, and a deep engagement with the natural world.